Nigeria Launches Military Med College to Fight Doctor Shortage

Nigeria’s healthcare crisis has a new battlefront. The Federal Government has announced plans to establish the Armed Forces College of Medicine and Health Sciences (AFCOM&HS), a dedicated military medical institution designed to simultaneously address the country’s catastrophic shortage of doctors and overhaul healthcare delivery within its defence forces a sector that, by official admission, currently has just 189 medical professionals serving a military population within a nation of over 240 million people.

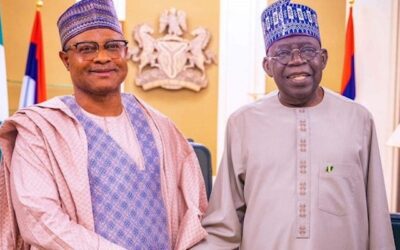

The announcement followed a high-level inter-ministerial meeting involving the Minister of Education, Maruf Alausa; the Minister of State for Education, Suiwaba Ahmed; and the Minister of Defence, Christopher Musa, alongside other key stakeholders drawn from the education, defence, and health sectors. The development was disclosed in a statement signed by the Director of Press and Public Relations at the Federal Ministry of Education, Boriowo Folasade, on Friday.

Nigeria’s doctor-to-patient ratio has for decades ranked among the most alarming on the African continent. The country has consistently lost trained medical professionals to emigration — a phenomenon widely described as brain drain — with thousands of Nigerian doctors working in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, and the Gulf States. The World Health Organisation recommends a minimum of one doctor per 1,000 people. Nigeria, with a population now exceeding 240 million, falls catastrophically short of that benchmark.

According to the Federal Ministry of Education’s statement, Nigeria currently faces a deficit of approximately 340,000 doctors. This figure represents not merely a healthcare policy failure but a public health emergency that has played out in the form of overwhelmed hospitals, inadequate emergency response systems, and preventable deaths across the country’s thirty-six states and the Federal Capital Territory.

The country’s medical training capacity has also been a structural bottleneck. For decades, annual admissions into medical schools hovered at levels that could not keep pace with population growth, let alone reverse the compounding deficit caused by emigration and retirement of existing practitioners. Against this backdrop, the announcement of AFCOM&HS represents one of the most ambitious single interventions in Nigeria’s medical training architecture in recent memory.

While the national shortfall is staggering, the situation within the Armed Forces is, by any standard, dire. The ministry’s statement noted that despite the country’s population exceeding 240 million, “only 189 medical professionals currently serve within the Defence Forces.” This figure points to a profound structural gap in military healthcare one with direct consequences for operational readiness, troop welfare, and the capacity of Nigeria’s military to respond to the country’s growing internal security challenges, from insurgency in the Northeast to banditry in the Northwest and maritime insecurity in the South.

Nigeria’s military has been under sustained pressure over the past decade. The Boko Haram insurgency, the rise of the Islamic State’s West Africa Province, the resurgence of armed banditry, and persistent agitation in parts of the South have kept the Nigerian Army, Navy, and Air Force in near-continuous operational deployment. Combat casualty management, trauma care, and field medicine under such conditions require a dedicated, well-trained corps of military medical professionals a corps that, on current numbers, barely exists.

The proposed Armed Forces College of Medicine and Health Sciences is described in the ministry’s statement as “a strategic national intervention to strengthen military healthcare services, address critical manpower shortages within the Armed Forces, and expand Nigeria’s overall medical training capacity.” The statement adds that the institution “will further position Nigeria as a regional hub for military medical training in West Africa.”

The college is designed to produce a specific category of medical professionals — those trained not merely in clinical medicine but in the specialised demands of military environments. According to the government, the college will build what it described as a sustainable pipeline of combat casualty-trained doctors, surgeons, trauma specialists, emergency response medics, military public health and disaster response professionals, and allied health personnel.

This approach reflects a global best practice in military medicine. Countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Israel, and India operate dedicated military medical institutions whose graduates are embedded directly into their armed forces, trained to function in both peacetime hospital settings and active conflict zones. Nigeria’s proposed AFCOM&HS would, if fully realised, place the country alongside these nations in maintaining a professionalised military medical corps.

One of the more technically significant aspects of the announcement is the decision to situate the new college within the existing university framework of the Nigerian Defence Academy (NDA) in Kaduna, rather than establishing it as an entirely new tertiary institution. This decision is deliberate and legally necessary.

The Federal Government has maintained a seven-year moratorium on the licensing of new universities, a policy intended to ensure that existing institutions are properly funded and developed before the tertiary education landscape is further fragmented. The ministry’s statement confirmed that the college “will operate within the existing university framework of the Nigerian Defence Academy in compliance with the Federal Government’s seven-year moratorium on new tertiary institutions and in line with the directive of President Bola Tinubu.”

The NDA, established by decree in 1964 and located in Kaduna, is Nigeria’s premier military institution for officer training. It currently offers degree programmes in the sciences, engineering, arts, and social sciences, and has the institutional infrastructure to support an expanded academic mission. Tying the new medical college to the NDA’s existing accreditation and governance structure reduces bureaucratic friction, leverages existing physical infrastructure, and allows the government to move more quickly toward operationalisation.

Clinical training, however, will not be confined to the NDA campus. The statement confirmed that medical cadets will receive clinical instruction in accredited federal and military hospitals, ensuring exposure to real-world patient volumes and a range of clinical conditions required for proper medical training.

Admission into the Armed Forces College of Medicine and Health Sciences will follow the standard national pathway. Prospective cadets will apply through the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board, the same body that coordinates admissions for all public universities in Nigeria. This decision ensures that admissions remain transparent, standardised, and competitive and that the institution draws from the same national pool of qualified candidates as other medical schools.

Upon graduation, medical cadets will be commissioned as Captains in the Armed Forces — a rank that reflects the length and rigour of medical training and the level of professional responsibility attached to it. This commissioning framework mirrors the approach used in countries with established military medical colleges, where graduating physicians enter service at an officer grade commensurate with their qualification.

The establishment of AFCOM&HS does not exist in isolation. The federal government disclosed that, as part of broader education and healthcare reforms, annual medical school admissions across Nigeria have already been increased from approximately 5,000 to nearly 10,000. Projections suggest this figure will be scaled further to approximately 19,000 in the coming years.