Flip Today, Reverse Tomorrow: What’s Broken in Nigeria’s Education Policymaking?

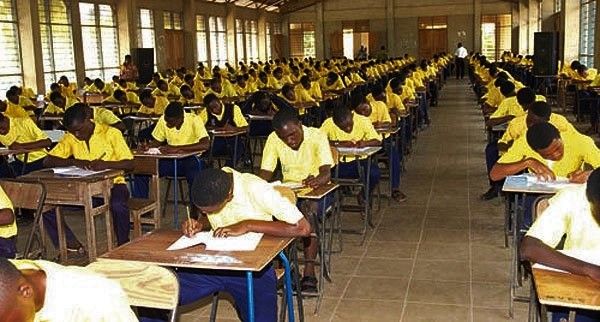

According to media reports, the Senate recently summoned Tunji Alausa, Minister of Education, and Amos Dangut, Head of the national office of the West African Examinations Council (WAEC), over new guidelines for the 2025/2026 Senior Secondary Certificate Examination (SSCE). The resolution followed a motion sponsored by Sunday Karimi, senator representing Kogi West, who said the guidelines altered subject requirements for senior secondary students preparing for the 2025/2026 May/June examinations. Karimi warned that the sudden changes to the guidelines could lead to mass failure, noting that candidates would be compelled to sit for papers for which they were not adequately prepared.

According to media reports, the Senate recently summoned Tunji Alausa, Minister of Education, and Amos Dangut, Head of the national office of the West African Examinations Council (WAEC), over new guidelines for the 2025/2026 Senior Secondary Certificate Examination (SSCE). The resolution followed a motion sponsored by Sunday Karimi, senator representing Kogi West, who said the guidelines altered subject requirements for senior secondary students preparing for the 2025/2026 May/June examinations. Karimi warned that the sudden changes to the guidelines could lead to mass failure, noting that candidates would be compelled to sit for papers for which they were not adequately prepared.

“The guidelines require that all SS3 students nationwide are required to adopt the new curriculum immediately, even though the guidelines were initially scheduled to operate in the next two years and apply to pupils who are currently in SS (senior secondary school) one and who are scheduled to write WAEC SSCE in 2027/2028,” he said.

“Subjects such as computer studies, civil education, and ‘all previous trade subjects’ have been removed from the WAEC (West African Examination Council’s) senior secondary school certificate examination, as the courses are no longer offered or to be examined in the exams slated for May/June 2026, despite years of preparation by senior secondary school pupils in Nigeria.

“With the removal of these three subjects (computer studies, civic education and all previous trade subjects), all pupils across all specialisations and combinations (be it sciences, humanities or business courses) are left with a maximum of just six courses each, despite the examination council’s requirement of a minimum offering of eight and maximum offering of subjects/courses for WAEC senior secondary certificate registration and examination.

“This implies that each pupil will have between two and three courses to be examined upon in May/June next year, despite never offering the courses before, and with abysmal preparation.

“Although the introduction of new trade subjects such as beauty and cosmetology, fashion design and garment making, livestock farming, computer hardware and GSM repairs, solar photovoltaic installation and maintenance, and horticulture and crop production are commendable, insisting that students without prior education on these subjects should be examined thereon in May/June 2026 will have negative implications on the students’ exams and quality of examination results and standards.”

In addition, Nigeria’s Education Ministry has seen recent policy shifts, notably reversing the 2022 mother-tongue instruction policy to reinstate English as the primary language of learning, citing poor performance data, and facing backlash for it. Another notable flip involved initially suggesting Mathematics wasn’t compulsory for Arts students, then quickly clarifying it remains essential for O-Level entry, attributing the confusion to miscommunication.

The issue of Nigeria’s university entry age that revolved around flip-flopping age requirements, from 16 to 18 and back to 16, with the current Minister of Education, Dr. Tunji Alausa, formally setting the minimum at 16 years, reversing a previous attempt by a predecessor to raise it to 18

Nigeria, a nation rich in culture and diversity, has long struggled with the efficacy of its education system. The country’s education policies have been marked by inconsistency, short-term thinking, and a lack of coherence, resulting in profound consequences for its youth and broader societal development. This article explores the intricate challenges within Nigeria’s education policy-making framework, examining the historical context, systemic flaws, and potential pathways toward reform.

To understand the current state of Nigeria’s education policies, it is essential to delve into their historical evolution. The country inherited an education system from the British colonial rule that was primarily designed to serve the needs of the colonial administration. Post-independence, Nigeria’s educational focus shifted towards national unity and economic development. However, the various military regimes and democratic governments that followed displayed a consistent pattern of neglecting the education sector, often prioritizing immediate political gains over long-term planning.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Nigeria experienced significant economic challenges, leading to drastic reductions in funding for education. The introduction of policies such as the Universal Primary Education (UPE) seemed ambitious but ultimately fell short due to insufficient planning and execution. While the 2004 National Policy on Education aimed to address these gaps by promoting access and improving quality, the resultant reforms lacked integration with local contexts and often failed to engage key stakeholders.

One of the critical challenges facing Nigeria’s education policy-making is the disconnect between policy formulation and implementation. Policies are frequently developed in isolation from the realities on the ground. For instance, while new curricula may be introduced, teachers often receive inadequate training to deliver them effectively. This lack of alignment leads to situations where students graduate without the necessary skills or knowledge to thrive in a competitive world.

Moreover, corruption plays a significant role in undermining education policy initiatives. Significant funding is often siphoned off before it reaches schools, particularly at the state level. This corruption not only deprives schools of essential resources but also fosters an environment of distrust among educators and policymakers. Efforts to introduce accountability mechanisms and transparency in budget allocation have been met with resistance, further compounding the issues.

Additionally, Nigeria’s education policies frequently exhibit a reactive rather than proactive stance. Political leaders often implement changes based on societal pressures or international trends rather than thorough analysis and strategic planning. For example, the introduction of free secondary education appears beneficial, but without accompanying infrastructure and teacher training improvements, the initiative is often rendered ineffective.

Another major issue plaguing Nigeria’s education policy-making is the inconsistency of educational standards across the nation. Nigeria is a large and diverse country, with significant regional disparities in educational resources and access. While urban centers may enjoy relatively strong educational institutions, rural areas often suffer from inadequate facilities, poorly trained teachers, and limited educational materials.

The lack of centralized oversight and effective regulation exacerbates this inconsistency. The Federal Ministry of Education provides guidelines, but states have substantial autonomy, leading to a patchwork of standards and practices. Consequently, the quality of education can vary significantly from one region to another, creating a divide that perpetuates cycles of poverty and underdevelopment.

Effective education policy-making requires the engagement of a broad spectrum of stakeholders, including teachers, parents, students, and community leaders. However, in Nigeria, there is often a considerable gap between policymakers and the communities they serve. Many policies are developed without adequate consultation with those who are most affected, resulting in a lack of ownership and commitment to the implementation of such policies.

For instance, teacher training programs are frequently designed without input from practicing educators, who possess invaluable insights into the challenges faced in classrooms. As a result, these initiatives may overlook critical aspects of teaching and learning, leading to ineffective outcomes.

Furthermore, the exclusion of parents and communities from the decision-making process can hinder the success of education reforms. When families feel disconnected from educational policies, they are less likely to support or engage with schools. Building partnerships with communities and fostering a sense of collective responsibility for education can enhance accountability and improve outcomes.

To address the issues within Nigeria’s education policy-making, below are key recommendations:

1. Strengthening Implementation Frameworks: Policies must not only be well-formulated but also accompanied by robust implementation frameworks. This includes establishing clear guidelines for execution, training for educators, and assessment mechanisms to ensure that policies are meeting their objectives.

2. Enhancing Transparency and Accountability: Foster a culture of transparency in funding and resource allocation within the education sector. This can involve the introduction of public tracking systems for education budgets and expenditures, empowering civil society organizations to monitor and report on the effective use of resources.

3. Decentralized Decision-Making: While federal guidelines can provide a baseline, allowing states and localities greater control over educational decisions can lead to more contextually relevant solutions. This decentralized approach would enable regions to tailor educational strategies to their specific needs, thereby addressing disparities in access and quality.

4. Inclusive Policy Development: Stakeholder engagement should be an integral part of the policy-making process. This entails actively involving teachers, parents, and community leaders in discussions about educational reforms. Feedback loops can ensure that policies are grounded in the realities of the classroom and community.

5. Investing in Teacher Training and Development: As the backbone of any education system, teachers must receive ongoing professional development to improve their skills and methodologies. Investing in comprehensive training programs that incorporate contemporary teaching practices will enhance educational quality across schools.

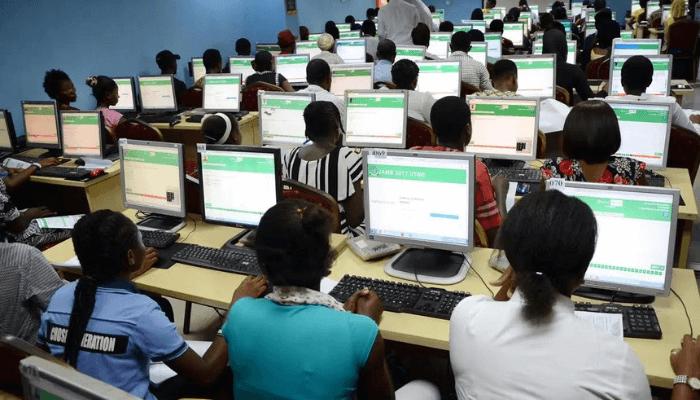

6. Leveraging Technology in Education: The integration of technology in education can help bridge gaps in access and improve teaching methodologies. Online platforms and digital resources can supplement traditional learning, particularly in remote areas with limited educational infrastructure.

In conclusion, Nigeria’s education policy-making is beset by challenges ranging from inconsistent standards and systemic corruption to a lack of stakeholder engagement. However, by acknowledging these issues and implementing comprehensive reforms, there is an opportunity to create a more effective and equitable education system. Engaging stakeholders, enhancing transparency, and tailoring policies to local needs are critical steps in transforming Nigeria’s educational landscape. If Nigeria can flip the narrative today, it might just reverse the tide of educational stagnation tomorrow. By committing to meaningful reforms, the nation can pave the way for a brighter future for its youth and ultimately, its society as a whole.