How Did They Get Here? A Lecturer’s Lament on Nigeria’s Academic Decline

How Did They Get Here? A Lecturer’s Lament on Nigeria’s Academic Decline

How Did They Get Here? A Lecturer’s Lament on Nigeria’s Academic Decline

I have spent over seven years teaching in secondary schools across Kaduna and Ibadan, and the last two years lecturing at the university. This means I have seen Nigeria’s education system from both ends. I have taught teenagers still struggling to understand simple sentences, and I now teach undergraduates who are expected to question ideas, defend arguments, and think independently. What I see daily in the university classroom is no longer just the problem of weak preparation; it is something deeper and more disturbing. Many students arrive in higher institutions unable to handle tasks they should have mastered long before admission. Basic understanding, focus, curiosity, and critical thinking are missing, yet these students come fully certified as “qualified.”

This growing gap between certificates and actual ability raises difficult questions about where our education system is failing, and who exactly should take responsibility.

This concern is not based on theory or nostalgia. It comes from experience. I have been in university classes where students cannot spell simple words or read a paragraph smoothly. I have met undergraduates who cannot name the President of Nigeria, do not know the governor of their own state, or cannot state their local government area. These are not trick questions or advanced civic tests. They are basic knowledge expected of anyone ready for higher education.

More worrying is the collapse of independent thinking. Many students cannot complete assignments unless they copy directly from classmates or submit material downloaded from the internet without understanding it. Thinking through a problem, organising ideas, or expressing an original opinion now feels unfamiliar to many students. This problem did not suddenly appear, but what was once occasional has now become pervasive. In a class of twenty students, it is sometimes difficult to find more than one average performer. Not an excellent student, not even an “A” student, just one who meets basic expectations.

This is the dissonance that demands explanation. These students did not fall from the sky. They were taught, promoted, examined, certified, and passed along every rung of the educational ladder before arriving at the university.

My worry, then, is not a personal lament. It is a diagnostic symptom. When lecturers across disciplines, institutions, and regions report the same academic anemia, we are no longer dealing with isolated cases or generational exaggeration. We are confronting a system that is quietly eating its own foundations while insisting everything is fine.

Some argue that weak students exist everywhere and that this is simply the reality of mass education. That may be true. But the problem here is scale. When poor academic ability becomes the norm rather than the exception, when universities can no longer assume basic literacy or civic awareness, the issue is not global trends but systemic failure.

Blame is attractive because it feels comforting. But education systems rarely collapse because of one person or group. The decay is gradual. Students respond to incentives. When effort is not rewarded, promotion is automatic, and failure has no real consequences, disengagement becomes logical. A student who has never been pushed to read, write, or defend ideas will not suddenly change upon entering the university. Universities are not miracle centres; they build on what already exists.

Parents also have a role to play. Many have quietly withdrawn from their children’s academic lives. Homework is treated as a nuisance, reading as punishment, and struggle as cruelty. In the past, parents were not necessarily more educated, but they were more involved. Education was seen as a serious path to progress. Today, it is too often treated as a certificate to be obtained, not a discipline to be endured.

Teachers, especially at the secondary level, are caught in difficult conditions. Many are poorly paid, overstretched, and forced to work in systems that value compliance over competence. In such environments, even committed teachers struggle to do real teaching. At the same time, teaching has lost its prestige. When a society pushes its best minds away from the classroom, the quality of education inevitably suffers.

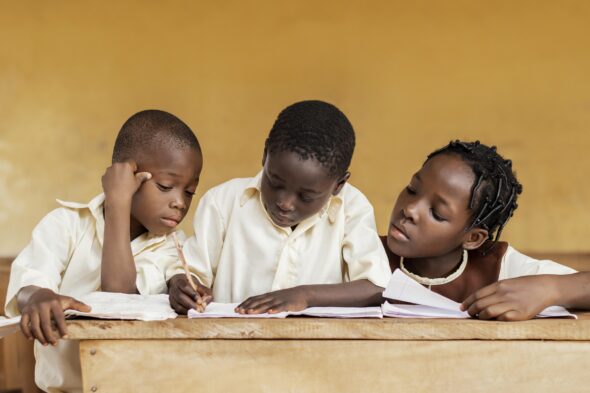

Yet the deepest problem begins earlier. Primary education is the foundation of everything. This is where reading, numeracy, discipline, and confidence should be built. When these are weak, secondary schools spend their time patching gaps, and universities are left to manage academic emergencies. You cannot teach advanced ideas to students still struggling to understand basic texts.

School owners and administrators add another layer of trouble. Many private schools prioritise enrolment and parent satisfaction over academic standards. Teachers who insist on discipline are labelled “too strict,” results are adjusted, and failure is negotiated away. Education slowly becomes customer service, and intellectual discomfort becomes unacceptable.

Then there is government oversight, or the lack of it. Standards mean little without enforcement. When monitoring is weak and consequences are rare, mediocrity spreads easily. Certificates lose their value when they are no longer tied to real competence.

So, who is to blame? Everyone, and that is the tragedy. Shared responsibility has produced shared avoidance. Each level passes the problem on, and the student arrives at the university carrying years of neglect.

Universities, in turn, inherit not students but educational debt. Lecturers are forced to choose between lowering standards or maintaining them while watching failure rates rise. Neither option is healthy.

The hard truth is this: Nigeria no longer has an access-to-education problem. It has a seriousness-of-education problem. Schooling has expanded faster than discipline, and certificates have increased faster than competence. Attendance has replaced learning, and promotion has been mistaken for progress.

Education systems rarely collapse loudly. They fail quietly, through students who cannot think clearly, read deeply, argue coherently, or care consistently. When this becomes common, the future is no longer hanging in the balance; it is already tilting.

Real reform will not come from louder blame, but from restoring standards. Promotion must be tied to competence. Reading and writing must be mastered early. Teachers must be treated as professionals. Parents must return to active academic involvement, and the government must move beyond paperwork to real accountability. Without these basics, every reform discussion is cosmetic.

Education only works when effort matters, failure teaches, and thinking is not optional.

Seun Perez Adekunle is a Political Science and International Relations lecturer who writes from Ibadan.