Daniel Otera

When Chief Cornelius Olatunji Adebayo emerged as governor of Kwara State in October 1983 under the platform of the Unity Party of Nigeria (UPN), it marked a rare political departure in the state’s post-independence history. Adebayo, a Christian from Kwara South, defeated the incumbent, Adamu Attah of the National Party of Nigeria (NPN), in what many observers considered a significant political upset. His election was seen as a breakthrough for non-Muslim minorities in a state whose political structure had long been shaped by northern Islamic cultural influence and emirate dominance. The moment was brief but symbolically powerful.

However, Adebayo’s tenure was abruptly cut short by the military coup of 31 December 1983, led by then Major General Muhammadu Buhari. The return to military rule suspended democratic governance and, with it, any immediate prospect of religious diversity in the state’s top political office. Since that brief interruption, no Christian has governed Kwara State. Successive administrations in the Fourth Republic have continued a pattern of Muslim leadership, largely drawn from Ilorin and its political sphere of influence.

Despite democratic advancements, the political exclusion of the Christian community in Kwara has remained a lingering legacy of both colonial-era structures and post-1999 electoral realities.

More than four decades later, despite Kwara’s religiously diverse population, the state’s highest seat of power has remained firmly within the grasp of Muslim elite. Ahead of the 2027 governorship election, a wave of renewed agitation has emerged from the Christian community. But behind the public calls for inclusion lies a deeper question: why has no Christian come close to winning the governorship since 1983, despite the apparent demographic balance?

Despite the centrality of religion to Nigeria’s social and political identity, national censuses have consistently avoided recording religious affiliation since 1991. The National Population Commission (NPC) deliberately excluded religion and ethnicity from the 2006 and the aborted 2023 census exercises, citing concerns over national unity and political sensitivities. As a result, there is no official data on the religious breakdown of Kwara State or any other part of the country.

In the absence of authoritative census figures, researchers, religious institutions, and independent think tanks have relied on demographic projections, electoral trends, and household surveys to estimate religious distribution. Based on multiple independent sources, including interpretations of Nigeria’s Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) and regional voting patterns, Kwara is often described as one of the few states with near religious parity. Most estimates place the Muslim population in the state between 55 and 65 percent, while Christians are believed to account for 35 to 45 percent.

These figures, while unofficial, are widely cited in interfaith discussions, political strategy circles, and civil society reports. They help explain why the issue of representation remains a recurring theme in Kwara’s politics. Yet despite the significant Christian presence, the governorship has remained elusive for the bloc, raising questions about the deeper factors at play beyond simple demographics.

For many observers, the imbalance is less about numbers and more about structure. Kwara’s political dominance by Muslim elite, particularly from Ilorin and parts of the North, is reinforced by a combination of historical emirate influence, cultural affiliations, and entrenched zoning practices by political parties.

These mechanisms have shaped the power equation in ways that consistently exclude Christians from the top seat despite their numerical strength in parts of Kwara South and Central.

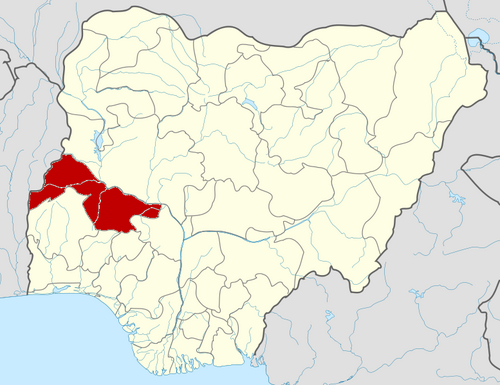

The political geography of Kwara State has played a defining role in how power is distributed. The state is divided into three senatorial zones: Kwara Central, which includes the capital city Ilorin; Kwara North; and Kwara South. Kwara Central, dominated by the Ilorin emirate and largely Muslim, has produced the bulk of the state’s governors, including those in the current democratic dispensation. Ilorin itself is deeply rooted in Islamic tradition, with longstanding historical and religious ties to northern Nigeria, particularly the Sokoto Caliphate. This legacy has entrenched a cultural and political consensus that heavily favours candidates from within that structure.

Although Kwara South contains a significant Christian population, particularly in areas such as Offa, Omu-Aran, and Oke-Ero, the zone has been largely excluded from power rotation discussions. Political parties across the spectrum including the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) and the opposition People’s Democratic Party (PDP) have frequently zoned their governorship tickets to Kwara Central and, occasionally, Kwara North. As a result, Christian aspirants from the South have struggled to find meaningful footholds.

Beyond zoning, cultural and religious networks have proven essential in securing political dominance. The emirate council in Ilorin, though not constitutionally empowered to dictate political affairs, wields enormous influence. Its endorsement or tacit approval often serves as a signal of legitimacy for candidates seeking office. This soft power is amplified by the extensive network of mosques, Islamic schools, and traditional associations that serve as voter mobilisation platforms during elections.

In contrast, the Christian community in Kwara remains politically fragmented. While the population is sizeable, the community is often split along denominational lines Catholics, Pentecostals, Anglicans, and Aladura churches each pursuing different social and spiritual goals with limited political coordination. There is no unified Christian political structure or mobilisation platform that matches the organisational scale of their Muslim counterparts.

Although official statistics on the religious composition of elected officials in Kwara State are rarely published, credible concerns have been raised about the underrepresentation of Christians in public office. In April 2020, the Kwara State chapter of the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) publicly stated that none of the state’s nine federal lawmakers, three senators and six members of the House of Representatives, were Christians. The association also noted that only six out of 26 commissioners and special advisers in the state executive council at the time were Christians, while no Christian was appointed to head any of the major boards, agencies, or commissions.

The pattern continues at the state legislature. Out of the 24-member Kwara State House of Assembly, only six are believed to be Christians, reflecting a consistent underrepresentation in lawmaking processes. At the local government level, while exact religious data remains unavailable, church groups and civic actors have continued to highlight the low number of Christian chairmen and councillors across the 16 LGAs.

Historically, Christian aspirants have struggled to secure the governorship ticket from major political parties in the state. One of the most notable attempts came in 2007 when Gbenga Olawepo-Hashim, a Christian and former deputy national publicity secretary of the People’s Democratic Party, contested under the Democratic People’s Party (DPP) and finished second to Bukola Saraki. His legal challenge to the election outcome was unsuccessful. Other Christian figures such as Theophilus Bamigboye and Gbenga Omotosho also made attempts at various times but were unable to secure broad party support or build strong political coalitions.

With 2027 drawing near, the question returns once again: can a Christian emerge as governor of Kwara State? Voices within the community have grown bolder. Leaders are now publicly stating their intention to push for equitable representation.

Reverend Cornelius Fawenu, who served as Special Adviser on Religious Affairs (Christian) under former Governor Abdulfatah Ahmed, has advised the Christian community in Kwara to begin early preparations ahead of the 2027 governorship election. Speaking in an interview published by The Guardian, Fawenu argued that Christians must move beyond reactionary politics and adopt a deliberate, long-term strategy. “Christian votes alone won’t win the election,” he said, emphasising the need to build coalitions across religious lines and present a credible, broadly acceptable candidate.

Shina Ibiyemi, a legal practitioner and spokesman for CAN in Kwara, also raised concerns about the underrepresentation of Christians in political structures. In the same report, he stressed that the agitation for a Christian governor should not be viewed through a narrow religious lens. “Politics should reflect our diversity. It is not a call for religious politics but for equitable participation,” he said, pointing to the absence of Christian voices in both the National Assembly and the state executive council.

Political parties in Kwara State have long been criticised for maintaining tightly controlled internal processes that favour entrenched elite. While party primaries are designed to promote internal democracy, in practice they are often orchestrated by powerful interests, particularly those concentrated in Ilorin, the state capital. These influential blocs comprising traditional rulers, political godfathers, and long-standing networks of party financiers frequently determine who emerges as candidate well before the primaries are formally conducted.

According to reports from Daily Trust and other national dailies, party primaries in Kwara have repeatedly drawn accusations of imposition, voter intimidation, and the sidelining of aspirants perceived as outsiders. In some cases, primaries have been marred by violence or boycotts. This closed-circle style of selection limits genuine competition and restricts the emergence of new voices, particularly from minority communities such as Christians concentrated in Kwara South and parts of Kwara North.

As a result, aspirants who are not part of the prevailing Ilorin-centric consensus regardless of their competence, religious identity, or political vision often find themselves edged out. The cumulative effect is a political culture where negotiation and allegiance to dominant blocs are often more decisive than electoral popularity or merit.

This systemic exclusion has fuelled growing frustration, particularly among Christian youth in areas such as Offa, Omu-Aran, and Oke-Ero, where community leaders increasingly speak of political marginalisation and neglect. Though Kwara has historically maintained a reputation for religious harmony, observers warn that continued exclusion from governance could breed disillusionment and resentment, especially among the younger generation.

“There’s a sense that decisions about our future are made elsewhere, without our input,” said a youth coordinator in Oke-Ero who asked not to be named. “When we vote, it feels symbolic. But when it’s time for real decisions like who flies the party flag, we are not even consulted.”

Security incidents in Christian-majority areas have further deepened this sentiment. In April 2025, the Kwara State House of Assembly raised alarm over increasing insecurity in local councils such as Oke-Ero, warning that banditry and kidnappings were threatening the state’s long-standing peace. Lawmakers argued that the failure of security intervention in these rural Christian communities could drive political apathy or even a breakdown of civic trust.

Political analysts fear that if the calls for inclusion are ignored, the agitation could be hijacked by extremist narratives or deepen sectarian fault lines, especially as the 2027 election draws closer. Kwara has, until now, avoided the kind of religiously motivated violence that has rocked other parts of northern Nigeria. But the signs of political fatigue and suppressed resentment, if left unaddressed, may challenge the state’s reputation as a bastion of interfaith coexistence.

To preserve stability and democratic integrity, many believe that political parties must reform their internal processes to reflect transparency, inclusion, and fairness. Otherwise, the state’s quiet discontent may become more difficult to contain.

For any meaningful shift to occur, the Christian community must do more than issue public declarations. It must unify, organise, and engage the political system from the grassroots level. This includes joining political parties in large numbers, supporting credible candidates, contesting at ward and local government levels, and forming strategic partnerships beyond the church walls.

Pastor John Damola of the Baptist Convention in Ilorin captured the stakes when he said, “It may appear insignificant today, but like a matchstick can set a hut ablaze, sustained agitation can ignite meaningful change. We must keep the hope alive.”