Daniel Otera

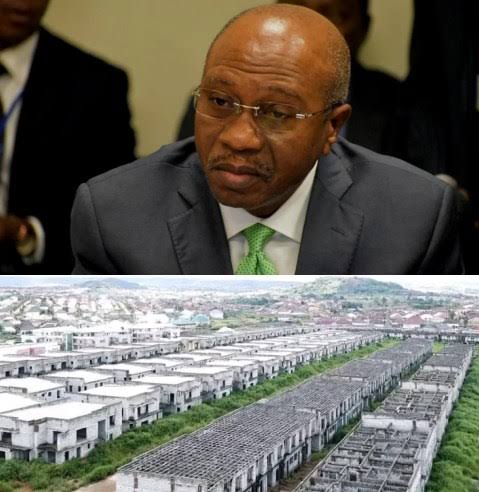

A fresh legal storm has hit the former Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), Mr Godwin Emefiele, as he stands trial over the alleged illegal acquisition of a massive residential estate in Abuja.

The case, now before a Federal Capital Territory High Court, has reignited debate about the unchecked accumulation of assets by public officials in Nigeria.

At the heart of the controversy is a sprawling estate comprising 753 duplexes, situated at Plot 109, Cadastral Zone C09, Lokogoma District. The property spans over 150,000 square metres an area roughly equivalent to 15 standard football fields.

The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) has arraigned Emefiele on an eight-count charge that includes criminal possession, forgery, and the concealment of illicit funds. Also named in the charge sheet is a certain “Ocheme,” who remains at large.

According to the EFCC, the accused maintained control over billions of naira stashed in proxy corporate accounts operated through Zenith Bank, allegedly tied to entities such as Kelvito Integrated Services and Ifedigo Integrated Services.

The agency claims these accounts were used to funnel proceeds from illicit financial activities linked to the former apex bank chief.

Mr Emefiele, who was granted bail to the tune of ₦2 billion, is required to provide two sureties with properties located in Abuja’s high-end neighbourhoods such as Asokoro, Maitama or Wuse 2. He has until Wednesday, June 12, to meet the bail conditions or risk being remanded at the Kuje Correctional Centre.

Although bail is a constitutional right and does not imply guilt or innocence, the sheer figures involved from the size of the property to the value of funds allegedly concealed have sparked public outrage and renewed scrutiny on elite accountability.

This is not Emefiele’s first brush with corruption allegations. Since his removal from office in June 2023, he has faced at least three other corruption-related charges.

Though Nigerian law guarantees the presumption of innocence, the recurring appearance of multi-billion naira assets linked to senior officials has reinforced public perception of a widening gap between official income and private wealth.

Court filings by the EFCC state that the Lokogoma estate if conservatively valued at ₦120 million per duplex, based on prevailing market rates could be worth over ₦90.36 billion.

The magnitude of such an acquisition raises a critical systemic question: How does a civil servant, operating within the bounds of public salary structures, accumulate such staggering wealth?

Though the Federal Capital Development Authority (FCDA) does not provide open-access registries of land transactions, court documents and asset forfeiture records indicate that Plot 109, Cadastral Zone C09, was originally allocated in September 2010 to a company named Windermere Nigeria Limited.

The allocation was ostensibly for mass housing development, in line with FCDA’s high-density residential zoning plans for the Federal Capital Territory.

Typically, the acquisition of such a parcel involves several stages, including technical site assessments, environmental impact evaluations, and the issuance of a Certificate of Occupancy (C-of-O). While the full paper trail in this instance is under judicial scrutiny, the EFCC argues that proxy ownership structures and concealed corporate interests form the backbone of its case.

According to the charge sheet, the EFCC alleges the possession of the following amounts in Zenith Bank accounts linked to Kelvito and Ifedigo Integrated Services:

₦1.23 billion

₦2.9 billion

₦1.98 billion

₦900 million

₦600 million

The funds, investigators say, were hidden using shell companies firms that often exist on paper but lack real business operations. This strategy mirrors previous cases involving high-profile figures like former Petroleum Minister Diezani Alison-Madueke and ex-National Security Adviser Sambo Dasuki, both of whom allegedly used similar mechanisms to obscure ownership of assets and cash flows.

According to financial crime experts, such proxies are emblematic of Nigeria’s wider problem with illicit financial flows, often made possible by regulatory loopholes and compromised oversight.

A forensic audit, if introduced during trial, could help trace transaction trails, authorisation flows, and uncover connections between the registered companies and the accused.

While Mr Emefiele maintains his innocence, the case casts a harsh light on institutional weaknesses within Nigeria’s regulatory and financial architecture.

As the governor of the CBN, Mr Emefiele oversaw the very systems now being examined for compliance failures. The implication that the country’s monetary gatekeeper may have engaged in the same financial misconduct he was tasked to prevent speaks volumes about the erosion of internal controls within public institutions.

Data from Transparency International’s 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index ranks Nigeria at 145th out of 180 countries—a stark indicator of public sector opacity. Despite the EFCC securing over 4,000 convictions in 2023 alone, the agency continues to grapple with limited success in asset recovery and systemic corruption prevention.

The Nigerian Financial Intelligence Unit (NFIU) also reported a 17% rise in suspicious transaction reports last year. However, only a small percentage of these cases translate into court-admissible prosecutions, underscoring the yawning gap between detection and deterrence.

The Emefiele case is more than a legal matter it is a mirror of Nigeria’s enduring crisis of governance. From real estate empires amassed by public servants to complex financial concealments that span banks and shell companies, the issue transcends personalities.

This trial, now adjourned till 11 July, offers an opportunity not just for accountability but for national reflection.

Unless systemic reforms are undertaken covering transparency in asset declarations, real-time financial surveillance, and enforcement of civil service lifestyle audits the cycle of impunity is likely to continue.