Temitayo Olumofe

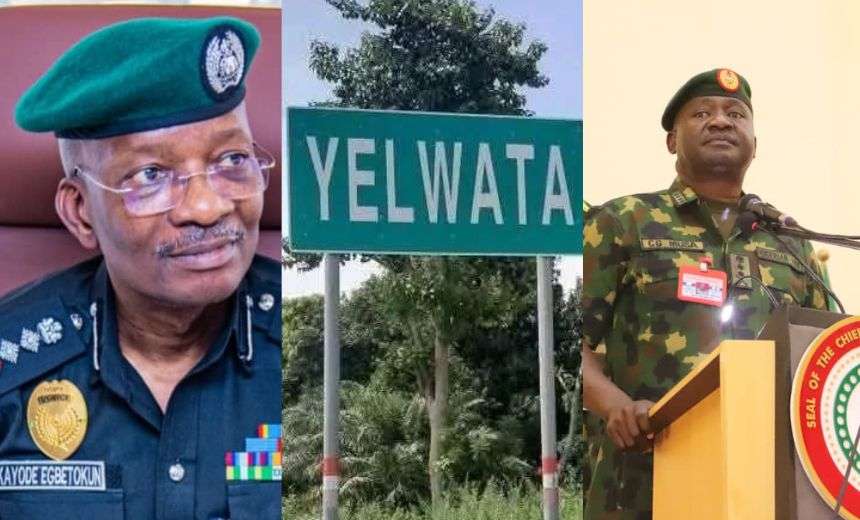

In the early hours of June 14, 2025, the small farming community of Yelwata in Benue State was turned into a nightmare. “We woke up to screams and the smell of smoke,” said one survivor, trembling as she recalled how armed men stormed her village, setting homes on fire and attacking anyone in their path. By morning, nearly 200 people— mothers, fathers, children— were dead, and the survivors were left with only the clothes on their backs and memories of loved ones lost.

This was not an isolated tragedy. According to Amnesty International for years, Benue State has been caught in a relentless cycle of violence. Between January 2023 and February 2024, there were at least 135 armed attacks, mostly by suspected herdsmen, resulting in more than 2,600 deaths. These attacks have destroyed homes, farmlands, and entire communities, leaving deep scars on the people who call Benue home.“Every day, we fear for our lives,” said another resident. “We just want to live in peace, to farm, to send our children to school.”

The attack on Yelwata was especially brutal because it exposed just how vulnerable Benue has become. On the night of the massacre, a severed telecom fibre line had left large parts of the state in total communication blackout. When the attackers arrived, there was no way to call for help. Even though Yelwata is guarded by a police station and three security checkpoints, the killers moved freely, overwhelming the few officers present.

Governor Hyacinth Alia described the attack as “insane carnage” and admitted that the state’s security system is overstretched. “Eyewitnesses tell us the terrorists don’t come in small numbers, they come in their hundreds,” he said. “We’re talking about over 200 motorbikes, with three or four armed men on each. That’s not just an attack; that’s an invasion”.

The aftermath was chaos. With no functional ambulance service, survivors had to rely on poorly equipped local clinics or chemists for first aid. Many government agencies, including the Benue State Emergency Management Agency, only arrived long after the violence, meeting survivors at Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps where they had fled for safety.

According to the National Emergency Management Agency, at least 1,069 households were affected by the most recent attack, and more than 6,500 people including pregnant women, lactating mothers, and hundreds of children were displaced and in urgent need of food, water, and medical supplies.

With each new attack, more people in Benue are calling for self-defense. “If the government cannot protect us, we must protect ourselves,” said a youth leader from Guma local government area. But Governor Alia has warned that this approach could lead to even more tragedy.

Yes, there’s a very grave need for defense, including self-defense, he acknowledged. “But let’s not be sentimental. We don’t want to end up with more deaths on our hands”.

Instead, Alia is pushing for community policing. “We should have started yesterday,” he said. “We know the right people to bring in at the local level, and this can be managed effectively if we act now”. He believes that empowering trusted locals who understand the terrain and the people will make it easier to spot threats and respond quickly.

Community policing means creating local security teams made up of people from the community, trained and supported by the government. These teams would work with traditional leaders and youth groups, using their knowledge of the area to keep watch and share information with the police.“With community policing, it becomes easier to identify those who understand the terrain and can be mobilised to join the ranks of the community police,” Alia explained.

However, he cautioned against untrained civilians taking up arms.

You need to be trained to understand the dynamics of fighting guerrilla warfare,” he said. “The Constitution permits all of us to defend ourselves, but to what extent? I cautiously advise my citizenry that it is not advisable to simply pick up knives, machetes, and sticks to fight. There are ongoing conversations around community policing; I am one of the governors who projected it”.

The Bigger Picture: Why Is Benue Bleeding?

Benue State sits at the crossroads of Nigeria’s north and south, making it a flashpoint for conflict between herders and farmers. Over the years, disputes over land and resources have turned deadly, with armed groups launching coordinated attacks on villages and farms. The violence has only grown worse, with Amnesty International reporting nearly 7,000 deaths in Benue between May 2023 and May 2025.

The state’s fragile infrastructure makes things even worse. Communication blackouts, poor roads, and a lack of emergency services mean that when attacks happen, help is slow to arrive—if it comes at all. “No centralised or well-coordinated emergency response systems exist in the state concerning these attacks,” said a local volunteer. “First responders are typically locals themselves, often aided by neighbouring communities”.

The trauma is everywhere. Children orphaned by violence, women widowed and left to fend for their families, and entire communities forced to live in IDP camps.

The scale of destruction and loss is heartbreaking,” President Bola Tinubu said after visiting Benue on June 18, 2025. “I see your pain; you’re not alone. I promise to work with Governor Alia to restore peace, rebuild the state, and bring justice to those who lost their loved ones”.

Can Community Policing Really Work in Benue?

Many people are hopeful that community policing will bring relief, but there are challenges. In the past, some local vigilante groups have helped reduce crime, but others have been accused of abusing their power. For community policing to work in Benue, it must be well-organized, properly funded, and closely supervised.

Governor Alia believes it can succeed with the right support. “This is no longer a conversation; it’s a necessity,” he said. “We need community policing, and we need it now”. He has called on traditional rulers, youth groups, and civil society to work together to make it happen.

The federal government has also promised to help, especially with intelligence gathering and tracking down those responsible for the violence. “With the federal government’s continued support through intelligence finding and searching, we will do even more. We will identify those people, apprehend them, and create a new narrative for our three local governments and, in fact, the state,” Alia stated.

But some residents remain skeptical. “We’ve heard promises before,” said a displaced mother of three. “What we need is action. We need to feel safe in our homes again.”

For community policing to bring real relief, several things must happen.

Training and Support: Local security teams must be properly trained and equipped, so they can respond to threats without putting themselves or others in danger.

Community Involvement: Traditional leaders, youth groups, and civil society must be involved in selecting and supervising community police members.

Government Backing: The state and federal governments must provide funding, resources, and oversight to prevent abuse and ensure accountability.

Emergency Response: Benue needs better roads, reliable communication networks, and functioning ambulance services, so help can reach victims quickly.

Justice and Reconciliation: Those responsible for the violence must be brought to justice, and efforts must be made to heal the wounds in affected communities.

A Glimmer of Hope Amid the Pain

Benue’s endless bloodshed has left thousands dead, families shattered, and communities living in fear. The attack on Yelwata was a wake-up call—a reminder that the current system is not working and that something must change.

Community policing offers a glimmer of hope, but it will only succeed if everyone— government, traditional leaders, and ordinary people— works together. As President Tinubu said, “I see your pain; you’re not alone.” The people of Benue deserve more than words. They deserve safety, justice, and a chance to rebuild their lives.