Hauwa Ali

Africa is confronting one of the most complex public-health landscapes in decades. As 2025 draws to a close, multiple, overlapping outbreaks of disease — from cholera and diphtheria to viral hemorrhagic fevers like Marburg — are converging with deep structural challenges in health systems, sanitation, immunization coverage, and conflict-driven instability. For millions of people, especially children and those in conflict zones, these emergencies are not distant headlines but daily realities.

Africa’s health landscape isn’t defined by a single emergency but by a continuum of threats that ripple across borders and systems. The Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) has repeatedly warned that multiple outbreaks, including cholera, mpox (formerly known as monkeypox), and Marburg virus disease, are straining response capacities and exposing deep vulnerabilities in public-health infrastructure. Growing mobility, displacement, and climate change further compound these risks.

The impact is widespread: weakened surveillance and laboratory systems, chronic shortages of essential supplies, gaps in routine immunization, and under-resourced emergency response capacities have helped many outbreaks escalate quickly. Vulnerable populations — women and children, displaced families, and those in conflict zones — are disproportionately affected.

Cholera — an acute diarrheal disease spread through contaminated water — has surged across multiple African countries, reaching levels not seen in decades. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) leads the crisis: the current outbreak has been declared the worst the country has faced in 25 years, with more than 64,000 cases and nearly 1,900 deaths recorded in 2025 alone. Children make up a sizeable share of the toll, and entire communities are reeling from lost lives, disrupted schooling, and overwhelmed clinics.

Cholera isn’t limited to the DRC. According to WHO reporting, Chad, South Sudan, Sudan, and other nations are also grappling with major outbreaks. Challenges here include poor access to clean water, inadequate sanitation, and health systems stretched thin by conflict and displacement. In some regions, fatality rates have climbed above 1 percent — a sign of delayed care and insufficient case management. This is a disaster that underscores a harsh truth: cholera is entirely preventable through basic water-quality improvements, sanitation infrastructure, vaccines, and community engagement. Yet the combination of climate shocks, urban overcrowding, and humanitarian emergencies has created conditions where this disease can flourish.

Another vaccine-preventable disease, diphtheria, has made a violent resurgence across Africa, despite decades of immunization progress. From January through early November 2025, more than 20,400 suspected cases and 1,252 deaths were reported across eight countries, including Algeria, Chad, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, and South Africa. Nigeria alone accounted for over 12,000 suspected cases and nearly 900 deaths, making it the epicenter of the outbreak.

Diphtheria was once rare in much of the world; the bacteria that cause it are preventable with routine childhood vaccines. But gaps in vaccine coverage — especially among displaced communities, marginalized populations, and areas with weak health services — have allowed the disease to reclaim territory. Reports indicate that large numbers of cases occur among children and young adults, with many having missed vaccination altogether. Compounding the problem, there is a global shortage of diphtheria antitoxin, a critical treatment for severe cases. Limited laboratory confirmation and testing capacity further complicate efforts to track and respond effectively. Health experts warn that without intensified immunization campaigns, community engagement, and strengthened health systems, the outbreak could continue its geographic spread well into 2026.

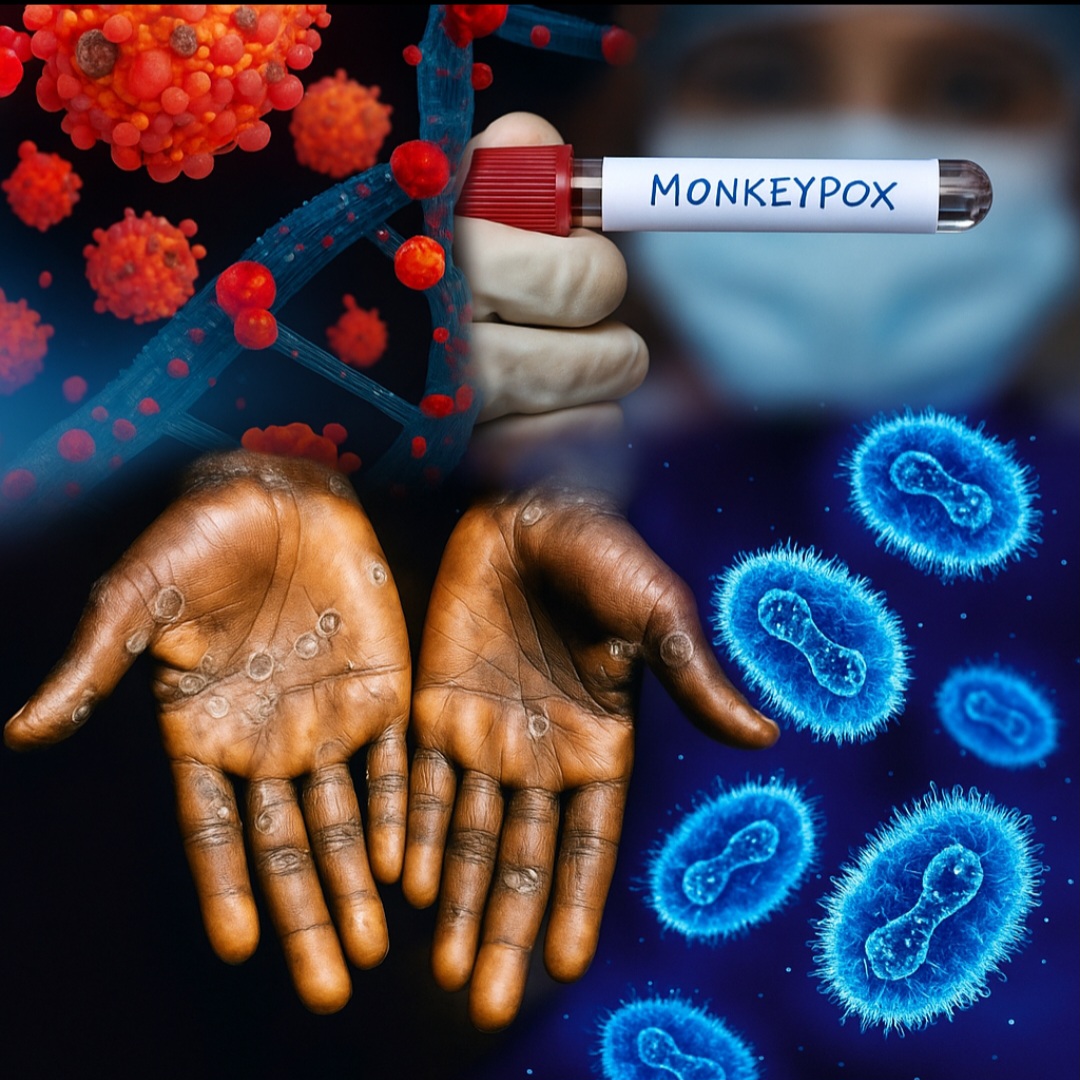

Once regarded as a rare viral infection, mpox became a global concern in recent years. In parts of Africa, it remains widespread — though with notable variation. Data shared by Africa CDC indicate that across the continent in 2025, there have been tens of thousands of suspected and confirmed mpox cases, with hundreds of deaths. Countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone, Uganda, and Liberia have reported the highest burdens.

Encouragingly, intensified surveillance, testing, and vaccination efforts have contributed to declines in transmission in some regions. Countries such as Côte d’Ivoire have gone weeks without new cases, and increased vaccine deployment has helped curb the spread in other hotspots. Yet mpox remains active in many areas, with ongoing risks of flare-ups where immunity gaps persist. Response strategies — including community health-worker training, targeted vaccination of high-risk groups, and expanded testing — have shown promise, but sustained investment is vital if gains are to endure beyond emergency response.

Marburg virus disease (MVD) is one of the most feared viral hemorrhagic fevers, similar to Ebola in severity and fatality risk. Unlike the DRC’s Ebola outbreaks, however, Marburg cases have been more scattered but not less concerning. In late 2025, health authorities confirmed an outbreak in Jinka Town, Southern Ethiopia, with several confirmed cases and a high fatality rate. Rapid-response teams, contact tracing, and increased surveillance have been deployed, but the potential for spread remains a serious concern given the virus’s high lethality and the challenges of healthcare access in remote areas. While outbreaks of Marburg are often localized, they require immediate, well-coordinated responses because of their potential to overwhelm fragile health systems and strike without warning.

While diseases like cholera and viral hemorrhagic fevers make dramatic headlines, long-standing threats like measles continue to burden countries with low immunization coverage. Parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo have seen sizeable measles outbreaks, resulting in thousands of infections and deaths in children. Measles outbreaks often signal deeper problems: declines in routine vaccination, missed opportunities for catch-up campaigns, and instability that disrupts health-service delivery. Worldwide, measles remains one of the most contagious infectious diseases. In Africa, where routine immunization coverage varies widely, gaps can quickly translate into widespread transmission. For public-health officials, preventing measles means strengthening routine childhood vaccination and rapidly responding to outbreaks with mass immunization drives.

Beyond acute outbreaks, persistent health threats like malaria and underlying systemic weaknesses further complicate Africa’s health-emergency landscape. The World Health Organization reports that malaria deaths increased in 2024, with most fatalities occurring in sub-Saharan Africa. Rising drug resistance, weakening prevention coverage, and funding shortfalls are major drivers of this trend. At the same time, chronic issues like malnutrition — often aggravated by conflict, drought, and food insecurity — make populations more vulnerable to infectious diseases and complicate treatment outcomes. Even where outbreaks are controlled, weak health systems struggle to absorb the added burdens of emergency response while continuing routine care, maternal and child-health services, and chronic-disease management.

Africa’s health emergencies are deeply entangled with humanitarian crises. In places like Sudan, ongoing conflict has decimated health infrastructure, disrupted services, and made outbreak control far more difficult. Attacks on hospitals and the displacement of health workers undermine routine immunization, disease surveillance, and emergency response — increasing the risk of secondary outbreaks. Conflict-driven displacement also concentrates vulnerable populations in overcrowded camps with poor water, sanitation, and hygiene conditions — perfect conditions for diseases like cholera and diphtheria to spread.

These realities highlight that disease outbreaks do not occur in a vacuum. They are shaped by political, economic, and security forces that determine access to care, public-health funding, and community resilience. The Africa CDC continues to lead continental surveillance and response efforts, working with national ministries of health, WHO, UNICEF, Gavi, and other partners to strengthen outbreak detection, case management, and immunization campaigns. Targeted vaccination drives, enhanced laboratory networks, and community engagement are central pillars of these efforts.

International partners are also stepping in with technical support, emergency funding, and vaccine supplies. For cholera, the WHO, the African Union, and global health partners are pushing for a continental elimination strategy focused on sanitation, clean-water access, and domestic investment. Yet experts stress that long-term resilience will require shifting from reactive emergency response to sustained investments in primary healthcare, health-workforce training, supply-chain systems, local pharmaceutical manufacturing, and digital-surveillance capabilities.

As 2026 looms, Africa’s health-emergency landscape remains volatile. Cholera continues its deadly march, diphtheria threatens to spread beyond current boundaries, viral hemorrhagic fevers lurk in remote communities, and vaccine-preventable diseases like measles still find fertile ground. The path forward is not simply biomedical. Strengthening health resilience means addressing clean-water and sanitation access, closing vaccine gaps, protecting health infrastructure in conflict zones, expanding community-health systems, and ensuring national and continental investment in health security.

Most importantly, the continent’s health future hinges on prevention — not just response. Ending outbreaks, reducing mortality, and building lasting capacity will require sustained political will, equitable resource allocation, and genuine partnership between African governments, communities, and international actors. Only with such commitment can millions of Africans move from surviving one emergency to building systems that prevent the next.