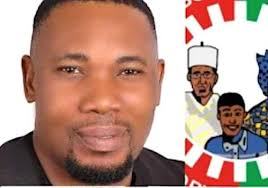

Modupe Olalere

Nigeria’s democracy turned a historic corner when Bright Ngene, a man currently serving a seven-year prison term, was declared the winner of the Enugu South Urban Constituency by-election on August 16, 2025. The bizarre development has unsettled the nation, provoking intense debate about the meaning of democracy and the sanctity of electoral laws in Nigeria. How can a legally disqualified candidate, incarcerated in prison, secure certification from the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) as winner of a legislative seat?

A Convicted Candidate’s Victory Against All Odds

Labour Party (LP) candidate Bright Ngene has been imprisoned since July 28, 2024, after the Enugu South Magistrate Court convicted him for misappropriating a ₦15 million community development fund in Akwuke, Enugu South Local Government Area. He received a seven-year jail term, which by law should disqualify him from contesting elections.

Yet, due to the loopholes in Nigeria’s electoral system, Ngene’s candidacy remained valid in the rerun election ordered after his 2023 victory was nullified over irregularities. In a dramatic twist, he once again defeated his opponent, Sam Ngene of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), by a margin of 3,000 votes. INEC accepted the results and issued a certificate of return — a move that has sparked outrage.

What the Law Says: Eligibility and Disqualification

Nigeria’s 1999 Constitution (as amended) and the Electoral Act 2022 clearly stipulate who is qualified or disqualified from contesting elections.

Section 66(1)(d) of the 1999 Constitution disqualifies any person who “has been convicted and sentenced for an offence involving dishonesty or fraud” unless a period of 10 years has passed since the conviction.

Section 107(1)(d) (for State Houses of Assembly) restates the same prohibition.

Section 137(1)(e) (for the Presidency) and Section 182(1)(e) (for Governorship) echo the same disqualification for convicted persons.

Electoral Act 2022, Section 29(5-6) allows any person to challenge the eligibility of a candidate on grounds of constitutional disqualification.

Thus, in principle, Ngene’s conviction on charges of fraud-related offences renders him constitutionally ineligible to run for or hold legislative office. His victory raises questions about how INEC cleared him to contest despite his prison status.

INEC’s Role and Electoral Integrity Questions

INEC defended its role, insisting that it conducted the rerun as ordered by the court. Spokesman Sam Olumekun stated, “the polls were conducted as directed and declarations followed due process.” However, critics argue that INEC failed in its constitutional duty under Section 153(f) of the 1999 Constitution and Paragraph 15, Part I of the Third Schedule, which empower it to enforce electoral laws. By certifying a candidate disqualified under Section 107(1)(d), INEC stands accused of undermining both constitutional safeguards and electoral integrity.

Public Outrage and Democratic Contradictions

For many Nigerians, it is deeply troubling that someone serving a jail term could be declared a lawmaker. This incident fuels skepticism that Nigeria’s democracy is increasingly about “game politics” rather than genuine representation.

Some politicians, however, have framed Ngene’s victory as “the will of the people” prevailing against elite manipulation. Enugu APC chairman, Barr. Ugochukwu Agballah, described it as a victory for democracy, calling for legal measures to free Ngene so he could assume office.

Yet, electoral law is clear: his conviction makes him unqualified. His case highlights how weak vetting processes, political interference, and institutional loopholes compromise Nigeria’s democracy.

Loopholes and the Call for Reform

Ngene’s case is not an isolated incident but part of a larger systemic failure. Critics argue that Nigeria must urgently:

Strengthen pre-election screening: Ensure that candidates convicted of crimes under Section 107(1)(d) cannot contest, even if cleared by political parties.

Empower INEC legally and politically: Amend the Electoral Act 2022 to give INEC clearer authority to disqualify ineligible candidates without waiting for court intervention.

Establish automatic disqualification protocols: Prevent electoral victories by candidates who constitutionally lack eligibility, even if they secure the majority vote.

Reinforce judicial speed: Election petitions and qualification cases must be fast-tracked, to prevent ineligible candidates from wasting public resources by holding seats illegally.

Civil society organisations, lawyers, and political analysts insist this episode should be a turning point for Nigeria’s democratic reforms. Without plugging these gaps, elections risk being continuously undermined by court battles, confusion, and disillusionment.

Conclusion: Democracy at a Crossroads

The Enugu South Urban Constituency by-election exposes the fragile state of Nigeria’s democratic institutions. The election of a jailed man, in defiance of constitutional provisions, paints a troubling picture of a democracy in crisis.

Unless urgent reforms are enacted, Nigeria risks further erosion of public trust in its elections. As the Constitution itself states under Section 14(2)(a), “sovereignty belongs to the people.” Yet that sovereignty is hollow if flawed institutions allow ineligible candidates to override the rule of law.

The image of a jailed legislator-elect is now a stain on Nigeria’s democratic experiment. Whether this becomes a lesson for reform or another forgotten episode remains to be seen.