Hauwa Ali

For decades, Africa has waited at the end of the vaccine queue, receiving doses last and facing shortages first. The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare that injustice, exposing how global health systems too often fail the people who need them most.

Now, in the heart of Rwanda’s capital, a new chapter is taking shape. Backed by fresh European financing, BioNTech’s mRNA vaccine facility in Kigali is emerging as a symbol of what health equity can look like when power, capital, and technology begin to shift south.

With a €95 million package from the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Commission, the project marks more than just the start of local vaccine production; it signals a turning point in Africa’s long struggle to control its own health future.

“This is not charity, it’s equity,” said Dr Michael Olilo, a genetic engineer at Kenya’s Centre for Biotechnology Research and Development (CBRD). “It’s about ensuring that the ability to make life-saving vaccines isn’t determined by geography.”

The EIB financing—a mix of a €35 million grant from the European Commission and up to €60 million in EIB loans—falls under the EU’s Global Gateway strategy. It builds on a previous commitment from the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), which in May 2024 announced funding of up to US$145 million (≈ €130 million) to support BioNTech’s Kigali project.

To many public-health and biotech experts, this deal represents precisely what Africa’s vaccine ambitions have lacked: long-term, risk-tolerant capital that allows ownership and operations to stay on the continent.

“For years, Africa’s vaccine-production plans existed mostly on paper because the financing models didn’t fit,” says Olilo. “You cannot build self-reliance on short-term grants. This structure is different; it’s designed to last.”

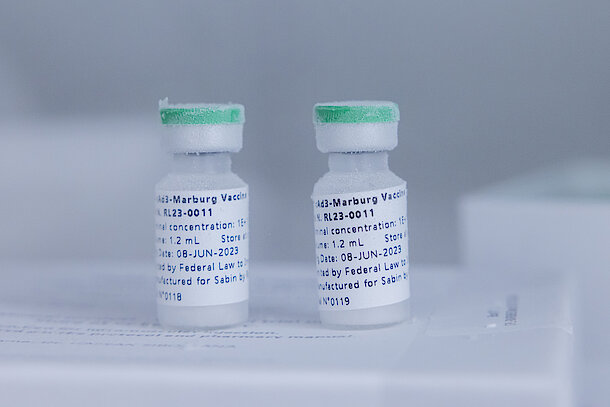

The facility in Kigali is the centerpiece of what is envisioned as a continent-wide mRNA vaccine ecosystem. Using BioNTech’s modular “BioNTainer” units, the site will produce vaccines targeting diseases that weigh heaviest on African economies and health systems, such as malaria, tuberculosis, HIV, and mpox.

The first modules arrived in Rwanda in 2023. Pilot production is targeted for the coming years (public estimates put early production around 2025–26). Once operational, the facility aims to serve both research and commercial roles: manufacturing for clinical trials, creating hundreds of high-value jobs, and transferring advanced biotech know-how to local scientists and technicians.

“The BioNTainer model is capital-efficient and scalable,” explains Olilo. “It allows production to grow with demand—and keeps both knowledge and economic value rooted in Africa.”

When COVID-19 struck, African countries were forced to wait months for vaccines as wealthier nations monopolised global supplies. By mid-2021, less than 2% of Africans had received a single dose. That experience turned vaccine access from a humanitarian issue into one of sovereignty and security.

In 2021, the African Union set a bold target: by 2040, 60% of all vaccines used in Africa should be produced on the continent. That ambition has since evolved into coordinated policy and industrial frameworks. Earlier this year, at the Africa CDC’s Vaccine Manufacturing Forum in Cairo, health ministers and industry leaders reaffirmed that goal and launched the Platform for Harmonised African Health Manufacturing (PHAHM), a mechanism designed to align policy, investment, and technology transfer across member states.

“The momentum has shifted,” says a senior AU health official involved in the forum. “It’s no longer about catching up. It’s about building an ecosystem that can sustain itself.”

The Kigali project is one node in a growing continental web of vaccine producers, each backed by tailored finance and policy support. In Senegal, the Institut Pasteur de Dakar is expanding its MADIBA vaccine facility with a US$45 million package led by the International Finance Corporation. The investment will triple output by 2026 and position Dakar as West Africa’s vaccine export hub.

In South Africa, Cape-Town-based Afrigen Biologics received a US$6.2 million CEPI grant in January 2025 to develop an mRNA vaccine candidate against Rift Valley fever.

Egypt is following suit: a partnership between Vaccine Biotechnology City, local producer MEVAC, and Dutch biotech Batavia Biosciences will begin production of measles-rubella and rotavirus vaccines, reducing imports and serving regional markets.

Smaller African biomanufacturers are also upscaling. Near Kigali’s biopharma hub, local startup Bio Usawa is deploying modular production units alongside BioNTainer systems; in Kenya, Daktari Biotechnology is investing in local vaccine and diagnostic production aligned with the Africa CDC’s New Public Health Order.

Together, these ventures are translating health innovation into tangible industrial and employment growth. At the heart of this movement is a new financial architecture. Instead of piecemeal aid, African vaccine manufacturing is being built on blended finance, pooled procurement, and performance incentives.

The EIB’s blended financing approach, combining grants and loans, is mirrored across the continent. The Cairo Communiqué established the African Pooled Procurement Mechanism (APPM), supported by Afreximbank and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, to aggregate vaccine orders and give African manufacturers predictable demand.

The communiqué also urged the Gavi alliance and UNICEF to source at least 30% of their African vaccine supply locally. To reinforce that goal, Gavi launched a US$1.2 billion African Vaccine Manufacturing Accelerator in 2024, offering direct incentives to WHO-prequalified local producers.

“This is the missing link,” said a Gavi official. “Without market certainty, you cannot build factories. This mechanism tells investors and manufacturers that Africa’s market is real and ready.”

According to Africa CDC mapping, between 25 and 30 vaccine-manufacturing projects are active across the continent, with more announced as investment flows increase.

The numbers justify a compelling case for a vaccine-manufacturing push in Africa.

The Global Fund’s Zero Malaria Economy report estimates that if malaria control efforts collapse, Africa could lose US$83 billion in GDP by 2030; however, if elimination succeeds, the continent could gain over US$231 billion in economic benefits.

Meanwhile, analysts project the African vaccine market could grow several-fold, from roughly US$1.3 billion today to several billion by 2030, as population growth, public health spending, and regional demand all rise.

In other words, vaccines are not just about saving lives; they’re about building industries.

“Each facility that comes online creates skilled jobs, drives research, and keeps value circulating within African economies,” said Olilo. “The Kigali plant is as much an economic story as it is a medical one.”

For Rwanda, BioNTech’s facility is a centrepiece of its Vision 2050 strategy—an effort to transform the country into a knowledge-driven, high-income economy.

Situated in the Kigali Innovation City, the site will anchor a biotech cluster linking universities, startups, and international partners. Local curricula are already being aligned with the new demand for skills in bioengineering, quality assurance, and pharmaceutical logistics.

Rwanda’s Health Minister has described the project as “a generational investment—one that positions Rwanda not just as a consumer of technology, but as a creator.”

Because BioNTech’s modular production concept is replicable, other countries—including Ghana, Kenya, and South Africa—are exploring partnerships to host future units, turning Kigali into the first hub in a network of African mRNA manufacturing sites.

Beyond bricks and machines, the Kigali facility represents a philosophical shift—from dependency to partnership. For decades, global vaccine-supply chains flowed one way: from labs in Europe, North America, and Asia, to clinics in Africa. Now the flow of technology, skills, and ownership is two-way.

“This is what health equity looks like in practice,” said a senior Rwandan health official overseeing the project. “It’s not about hand-outs. It’s about shared capability—and shared responsibility.”

When the Kigali site begins pilot production in the coming years, its first outputs may focus on clinical trial materials rather than mass-market doses. But the real measure of success will not just be the vaccines themselves—it will be the people trained, the systems built, and the precedent set. Analysts say the BioNTech model could be Africa’s blueprint for scaling local vaccine production quickly and efficiently.

“Africa needs more purpose-built facilities like Kigali,” Olilo says. “But it also needs a wider mix of investors, not just governments and development banks, but African pension funds, venture capital, and local equity. That’s how we’ll scale.”

By combining local ownership, modular design, and blended financing, the Kigali project has become a case study in how to operationalise health equity, not through aid, but through industry. As construction cranes rise over Kigali Innovation City and engineers begin assembling BioNTainer modules piece by piece, the vision that once seemed distant is now tangible.

If successful, the project will mark a historic shift—from a continent that depended on others for survival to one that can shape its own health destiny. For the millions of Africans who lived through the uncertainty of the pandemic, that shift carries quiet power. Because the next time the world scrambles for vaccines, Africa won’t be waiting in line. It will be making them.

“For the first time,” says Dr Olilo, “Africa isn’t just preparing for the next pandemic, we’re preparing to produce the solution.”