Mobola Johnson

Ogijo used to be one of those quiet border communities between Lagos and Ogun State where life ran on routine and familiarity. That rhythm changed the moment residents began noticing strange dust settling on their windows, unexplained illnesses in their homes, and a stubborn pattern of headaches and fatigue that no one could explain away. Over time, the truth emerged. A toxic problem had been growing right in front of them.

Investigations by state and federal regulators kept returning the same disturbing findings. Lead contamination was not just present; It was widespread. Samples taken from dust, soil, and even household surfaces repeatedly showed concentrations far above national and international safety limits. One joint assessment by the Ogun State Ministry of Environment and the National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency found lead levels exceeding allowable limits by more than twenty times in some locations.

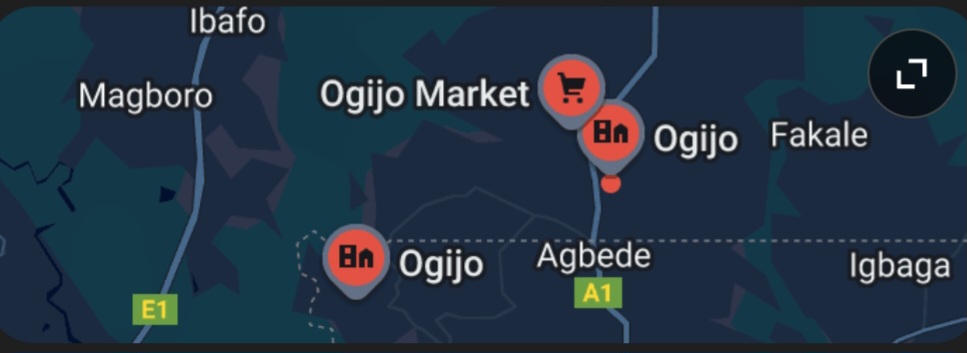

The source had been operating in plain sight. Several lead-acid battery recycling plants scattered around Ogijo had spent years dismantling and melting old batteries without adequate controls. Their smokestacks and breaking yards released fine, lead-laden dust that drifted into homes, farms, shops, and schools. The particles settled quietly into everyday life, building up year after year.

Lead is used in many industrial materials, and its health risks are well-documented. There is no safe threshold. Even the smallest exposure can accumulate in the bloodstream and in bones. Children face the greatest danger because their bodies absorb lead more quickly and their play habits place them in direct contact with contaminated soil and dust.

Doctors working with affected families say the symptoms rarely start dramatically. Parents first notice stomach cramps, persistent headaches, or their children suddenly struggling in school. At higher exposure levels, the consequences become severe, including neurological damage and lifelong developmental challenges.

Recent soil tests in and around Ogijo confirmed hazardous contamination. One school recorded 1,900 ppm of lead in its playground soil, a figure drastically higher than the 400 ppm threshold considered dangerous for children. Independent environmental groups and health organisations reported that household samples, farmland soil, and even roadside dust contained lead at levels capable of causing long-term harm.

Blood tests deepened the concern. In some screening exercises supported by health officials and civil society groups, nearly half of the children tested recorded blood lead levels associated with cognitive impairment. Many adults show elevated levels, too, despite having no direct contact with the factories.

Residents describe a predictable pattern of symptoms: unrelenting headaches, fatigue, abdominal pain, memory lapses, and sleep disturbances. These complaints are coming from families who were living near the industrial sites, not from workers inside them.

After years of community complaints and accumulating evidence, Ogun State finally moved against the major offenders. Seven battery recycling factories were shut down for violating environmental regulations and for operating without adequate pollution controls. Environmental officers also carried out stop-work orders and sealed additional facilities pending further investigation.

The federal government has stepped in as well. The Federal Ministry of Environment launched the National Lead Poisoning Prevention and Control Programme, while NESREA initiated enforcement actions and mandated full remediation plans from operators. The Ministry of Health opened a Lead Testing Centre at the Ogijo Primary Health Centre, offering free screenings for residents.

In Abuja, the Senate Committee on Environment conducted a fact-finding mission and classified the Ogijo crisis as a national public health emergency. Lawmakers urged immediate cleanup, mandatory environmental audits for all recycling plants, and criminal penalties for non-compliant operators.

These actions signal progress, but experts warn that shutting down factories does not remove lead from soil, water, or the bodies of residents. The contamination accumulated over the years, and the cleanup will require long-term effort.

Lead poisoning is preventable. The steps may be simple, but they matter.

• Get tested, especially children and pregnant women.

• Keep children away from bare soil in high-risk areas.

• Improve hygiene habits like washing hands before meals and removing shoes at the door.

• Use safer water sources where soil contamination may affect boreholes.

• Demand continuous monitoring and transparent reporting from local authorities.

• Spread accurate information. Awareness remains one of the strongest defenses.

Ogijo is not dealing with an abstract environmental problem. It is dealing with a crisis that has altered daily life, placed children at risk, and exposed the gaps in industrial oversight. Families are carrying consequences they never caused. Some healing has started, but the real test will be whether the promised cleanups, reinforcements, and monitoring actually continue.