Pius Nsabe

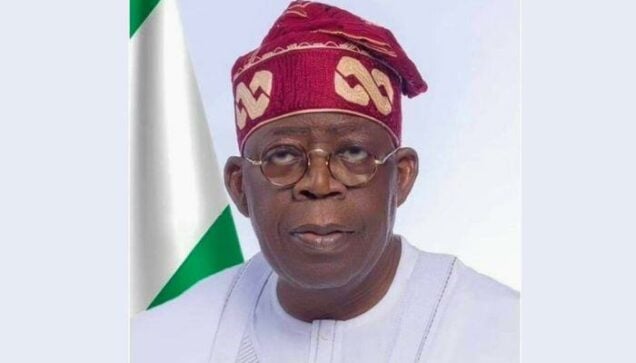

President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s recent decision to grant presidential clemency to 175 individuals, including high-profile figures such as Herbert Macaulay, Farouk Lawan, Maryam Sanda, Ken Saro-Wiwa, and Major General Mamman Vatsa, has ignited intense national debate about the nature, purpose, and morality of the prerogative of mercy in Nigeria’s political and justice system. While the exercise of presidential pardon is constitutionally recognised as an instrument of compassion and restorative justice, its application in this case raises critical questions about the balance between justice, political expediency, and national reconciliation.

The Nigerian Constitution, under Section 175, vests in the President the power to grant pardons, reprieves, and commutations on the advice of the Council of State or the Presidential Advisory Committee on the Prerogative of Mercy. Historically, this power has been exercised as a humanitarian tool to correct judicial excesses, reward genuine rehabilitation, or promote social harmony. However, like many such discretionary powers, it can also be susceptible to abuse, particularly when deployed to serve political or sentimental interests. President Tinubu’s mass pardon exercise has elements of both justification and controversy. On one hand, it embodies the spirit of mercy, acknowledging that some convicts may have demonstrated genuine remorse and transformation after years of confinement. On the other, it risks eroding public confidence in the justice system when individuals convicted of serious crimes are freed while victims and their families continue to live with the trauma of injustice.

In principle, clemency should reflect a moral vision of justice that seeks balance between punishment and forgiveness. In practice, however, it can send conflicting messages when the beneficiaries include those found guilty of grave offences such as murder, corruption, and abuse of public trust. For instance, the inclusion of individuals like Maryam Sanda, who was convicted for the murder of her husband, sparked public outrage, with many viewing the decision as an affront to the rule of law and the sanctity of life. Conversely, the posthumous pardons granted to environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and military officer Mamman Vatsa were widely applauded as symbolic acts of reconciliation and national healing, correcting historical injustices committed by past military regimes. This duality illustrates how the prerogative of mercy can simultaneously redeem and undermine a nation’s moral and legal order depending on its application.

From a legal standpoint, there is no question about the President’s authority to issue pardons. What is often debated is the criteria and transparency of the selection process. The Presidential Advisory Committee on the Prerogative of Mercy, headed by the Attorney-General of the Federation, claimed that each case was subjected to rigorous evaluation, considering factors such as the inmate’s behaviour, remorse, health, and contribution to prison reform. Yet, Nigerians have legitimate concerns about whether such recommendations are consistently objective or influenced by political connections and emotional lobbying. The absence of published guidelines, detailed reasoning, or public participation in the decision-making process leaves room for suspicion. It also raises a deeper ethical question about equality before the law—whether the mercy of the state is more accessible to the privileged and well-connected than to ordinary citizens languishing in overcrowded prisons for minor, nonviolent offences.

The sociopolitical context of this mass pardon cannot be ignored. Nigeria remains a country struggling with widespread corruption, insecurity, and public disillusionment in state institutions. In such an environment, any act of clemency that appears to favour elites or those convicted of capital crimes risks undermining public trust in governance. Pardoning known criminals or politically exposed persons can easily be interpreted as an attempt to sanitize the image of past allies or appease certain interest groups. In a society where impunity already runs deep, such decisions may embolden offenders to believe that crimes can be negotiated or forgiven through influence rather than accountability. When the line between mercy and impunity becomes blurred, the moral authority of justice itself begins to erode.

Nonetheless, the concept of clemency should not be dismissed entirely. In an overcrowded and underfunded correctional system like Nigeria’s, mercy can serve a rehabilitative and humanitarian purpose. Thousands of inmates are held under deplorable conditions for years without trial, and many of them are nonviolent offenders who deserve a second chance. Granting pardon to such individuals aligns with global trends in criminal justice reform that emphasize rehabilitation over retribution. In that sense, Tinubu’s action could be viewed as part of a broader effort to decongest prisons and promote restorative justice. But the credibility of such efforts depends on fairness and transparency—ensuring that mercy is extended based on genuine reform, not privilege.

From a moral and psychological perspective, the power to forgive should ideally reflect the collective conscience of society. A pardon should not trivialize the suffering of victims or diminish the seriousness of crime; instead, it should affirm society’s belief in redemption while maintaining respect for the law. By freeing individuals like Maryam Sanda, the administration risks sending a troubling message that remorse alone, without proportionate justice, is enough to erase wrongdoing. For the families of victims, such decisions can reopen emotional wounds, fostering resentment and distrust in the state’s commitment to justice. Meanwhile, the symbolic pardons for figures like Saro-Wiwa and Vatsa speak to the nation’s desire to reconcile with its past and restore dignity to those wronged by history. These contrasting cases show that clemency can either heal or hurt depending on the public perception of fairness and moral legitimacy.

Politically, President Tinubu’s mass pardon also aligns with his broader rhetoric of national unity and justice reform. By extending mercy to both the living and the dead, the administration appears to be invoking a narrative of forgiveness, inclusivity, and reconciliation. Yet, such symbolism carries political risk. In a democracy still haunted by inequality, selective mercy may be seen as hypocrisy. Critics argue that a true reform-minded government would focus on systemic justice reforms—speedy trials, humane prisons, equitable law enforcement—rather than headline-making pardons. The pardon of convicted politicians or controversial figures without parallel accountability reforms may thus be viewed as cosmetic, reinforcing cynicism about leadership sincerity.

In evaluating this decision, one must weigh the moral purpose of mercy against the necessity of deterrence. Justice systems function not only to punish but also to prevent crime by affirming consequences. When the state extends mercy too liberally to high-profile offenders, it risks weakening that deterrent effect. Nigeria’s persistent challenges—corruption, gender-based violence, and abuse of power—require strong and consistent enforcement of the law. Selective leniency could undermine the very principles the President claims to uphold, giving the impression that some lives and crimes matter less than others.

Ultimately, the 175 pardons granted by President Tinubu present a complex moral and political equation. Some of the decisions, particularly those rectifying historical wrongs or rewarding proven rehabilitation, are commendable and consistent with the compassionate side of governance. Others, however, appear to contradict the ideals of justice and accountability. The challenge before the administration is to ensure that future exercises of clemency are guided by transparent principles and an inclusive sense of fairness. Nigeria’s democracy cannot afford to let the prerogative of mercy become an instrument of political favour or moral confusion.

Clemency, when rightly applied, should inspire faith in the humanity of the state. When misused, it erodes confidence in justice and deepens the social fractures it was meant to heal. President Tinubu’s pardons have achieved both ends—offering closure to some, but reopening wounds for others. The ultimate judgment will depend not on the legality of the act, but on the integrity and transparency of its intent. In the eyes of a weary public yearning for justice, mercy must never appear as weakness or favouritism; it must stand as a testament to the state’s higher moral calling—a delicate but necessary balance between justice and compassion.